Contents

- 1.1 Introduction

- 1.2 Objectives

- 1.3 Background

- 1.4 Negotiating a Marketing Contract

- 1.5 Type of Marketing Contracts

- 1.6 Ledgers

- 1.7 Price Base for a Contract

- 1.8 Length of Contract

- 1.9 Premiums and Discounts

- 1.10 Flexibility

- 1.11 Summary

- 1.12 References

Authors:

Ron Plain, University of Missouri;

Glenn Grimes, University of Missouri

Reviewers:

John Lawrence, Iowa State University;

Chris Hurt, Purdue University;

Walt Swier, MFA Incorporated

Introduction

In the past decade there has been a rapid movement by U.S. hog producers and packers moving away from selling and buying hogs on the spot market. The decline in spot market sales has been offset by a steady increase in both contractual agreements between producers and packers and in packers raising hogs for slaughter. There are a number of reasons why producers have switched to contracts from spot market sales. First, it simplifies life. It is far easier, especially for larger hog operations, to negotiate a multi-year packer contract than to negotiate the price of every load of hogs. It is easier to arrange and budget transportation when all the hogs go to the same plant. A marketing contract assures shackle space. Perhaps most important, marketing contracts can offer a higher and more stable net price than the spot market.

Objectives

- Describe structural and marketing changes in the pork industry and their relationship with market price

- Outline different types of market contracts

Background

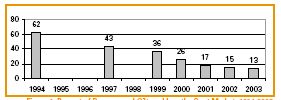

In the past decade there has been a rapid movement by U.S. hog producers and packers moving away from selling and buying hogs on the spot market (Figure 1). Surveys conducted by Glenn Grimes at the University of Missouri [1-2] indicate that in 1994, approximately 62% of barrows and gilts were sold to packers on the spot market. Three years later, in 1997, only 43% were. In 2000, Grimes found that 26% were spot market sales. USDA reported that 13% of packer purchases of barrows and gilts were made on the spot market in 2003 and 11.4% in the first quarter of 2004. Although the shift away from spot market sales has slowed, it does not appear to be over.

The decline in spot market sales has been offset by a steady increase in both contractual agreements between producers and packers and in packers raising hogs for slaughter. Nearly 21% of barrows and gilts slaughtered in 2003 were raised by firms that were also hog packers. In the last 25 years, a number of pork packers have gotten into hog production and in the case of Premium Standard Farms, a large hog producer has become a major packer. Of the nation’s six largest hog producers, four (Smithfield, Premium Standard Farms, Seaboard and Cargill/Excel) are also hog packers. Integrating production with packing offers advantages in quality control and traceability. A packing company that slaughters hogs it raises can provide its customers with more information about where and how the hogs were raised than can a packer that buys hogs from hundreds of different farms each day. Raising hogs not only provides packers with an assured supply of hogs with known characteristics, but stabilizes income since the profitability of hog packing and hog production are inversely related.

The declining number of hogs being sold on the spot market has created concern about the price discovery process, both for producers who sell hogs on the spot market and for those whose contract price is based in some manner on the spot market price. If the number of hogs sold on the spot market continues to decline, the industry will reach a point where the spot market price will no longer fulfill its role in the price discovery process, i.e. the spot market price will be too vulnerable to manipulation to serve as a basis for valuing the nation’s hogs. One approach to this price discovery problem is to switch from valuing hogs based upon the thinly traded spot market for hogs to valuing them based on the wholesale price of pork cuts, i.e. the cutout value. This alternative has two major shortcomings. First, sales of many pork wholesale cuts are also thinly reported. Second, this cutout value approach implies a constant margin for hog packers, which is something that packers may not be eager to accept.

Another approach is a regulatory fix. As part of the debate on the 2002 farm bill, the U.S. Senate passed a ban on packers owning cattle and hogs more than 14 days prior to slaughter. Although this provision was not included in the final law, it appears to be popular among small producers and is likely to be considered again by Congress. Another populist proposal discussed at the federal level is to require packers to buy a certain portion, e.g. 25%, of their daily kill on the open market. Since packer spot market purchases are already well below this level, such legislation would force many producers off of contracts they willingly signed. A similar approach that may have fewer negatives is to require producers to sell a certain portion of their hogs on the spot market. Each of these proposals would force a wider separation between production and slaughter of livestock. Individual states have also tried to regulate the relationship between packers and producers, sometimes with disastrous results for cattle and hog producers [3].

USDA’s mandatory price reports, which began in April of 2001, provide great detail on hogs purchased on a carcass weight basis by packers who slaughter over 100,000 hogs annually. In 2003, nearly 95% of barrows and gilts slaughtered under federal inspection were covered by mandatory price reporting. Each weekday, USDA reports data on six categories of hog slaughter: negotiated purchases (spot market sales), swine/pork market formula (a contract where the price is determined by a publicly reported hog or pork price, e.g. Iowa-Minnesota top or carcass cutout value), other market formula (a contract based on the lean hog futures contracts), other purchase agreements (all other producer marketing contracts), packer sold (from one packer to another), and packer owned hogs. The daily hog slaughter report can be obtained at: http://www.ams.usda.gov/mnreports/lm_hg201.txt.

Table 1 provides data for 2003 on percent of marketings, average carcass weight, and average percent lean by purchase category. USDA’s mandatory price reports indicate 13.28% of barrows and gilts slaughtered by reporting packers in 2003 were purchased on the spot market. Of the remaining barrows and gilts slaughtered that year, 20.93% were raised by packers and 65.79% were purchased under a packer contract. It is interesting to note that negotiated purchases tend to be smaller hogs and have a lower percent lean than contract purchases.

Larger hog operations are more likely to use marketing contracts than small firms. Lawrence and Grimes [4] found that three-fourths of hogs marketed by firms selling fewer than 3,000 head in 2000 were sold on the spot market. Less than 10% of hogs sold by the largest 156 U.S. hog producers were sold on the spot market in 2000.

Table 2 provides data on the average sort loss, average base price (before carcass premiums and discounts), average net price paid (including premiums and discounts) and standard deviation of net price for barrows and gilts purchased by packers reporting under USDA’s mandatory price reporting system in 2003. The average net price paid was highest for packer sold hogs and lowest for negotiated purchases. The standard deviation of net price paid was highest for negotiated hogs and lowest for hogs sold under other purchase agreements. The average base price for negotiated purchases was slightly higher than for swine/pork market formula hogs; but the net price for negotiated hogs was lower because the negotiated hogs on average were smaller and less lean.

There are a number of reasons why producers have switched to contracts from spot market sales. First, it simplifies life. It is far easier, especially for larger hog operations, to negotiate a multi-year packer contract than to negotiate the price of every load of hogs. It is easier to arrange and budget transportation when all the hogs go to the same plant. A marketing contract assures shackle space. This is especially important during periods like the fourth quarter of 1998 when slaughter capacity is exceeded. Perhaps most important, as Table 2 indicates, marketing contracts can offer a higher and more stable net price than the spot market.

Packers benefit from marketing contracts by having an assured supply of known quality hogs. Contracts also permit packers to cut expenses by reducing the number of hog buyers and buying stations. Packer’s willingness to share these savings with producers is one reason that contract prices average higher than spot market hog prices. Another likely reason contract prices have exceeded spot market prices is packers offered generous contracts in the past because they over-estimated future hog prices. Few people in 1997 could have correctly predicted that live hog prices during the next 6 years would average under $39/cwt. As a general rule, newer marketing contracts are less generous to producers than ones written in the 1990s.

One important side affect of the declining number of hogs sold on the spot market is that the spot market bid price is no longer a good measure of producers’ financial situation. In 2003, the average negotiated base price for barrows and gilts was $52.00/cwt and the average net price received by producers for barrows and gilts sold under all marketing arrangements was $55.21/cwt. The $3.21/cwt difference is significant given the breakeven price was approximately $54/cwt in 2003. The base price for negotiated sales implies the average producer lost roughly $2 per hundred pounds of carcass weight on each hog sold in 2003. The average net price indicates the average hog sold for about $1.20/cwt above breakeven.

In addition to the prior day slaughter report summarized in Tables 1 and 2, USDA also issues a number of reports on purchase prices. These reports are available over the internet at: http://www.ams.usda.gov/LSMNpubs/index.htm. Each weekday, four reports are issued on the price paid for hogs purchased before 9:30 am central time. These reports are for the eastern corn belt, the western corn belt, Iowa and Minnesota, and the entire nation. A comparable four reports are issued in mid afternoon for hogs purchased before 1:30 pm central time. The final four reports on prior day purchases are issued by 8 am each weekday morning.

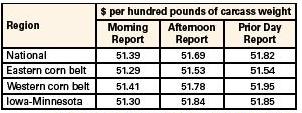

As Table 3 shows, prices paid tend to increase as the day progresses. The national average negotiated price in 2003 for barrows and gilts purchased before 9:30 am was $0.30/cwt lower than for those purchased before 1:30 pm, which in turn was $0.13/cwt lower than the average for the entire day. In 2003, the number of barrows and gilts included on the morning reports was equal to 20.57% of the total included on the prior day reports. The number included on the afternoon reports equaled 71.69% of the prior day reports. Thus, 28.31% of hogs were purchased too late in the day to be included on either the morning or afternoon reports. Simple calculations indicate that the national average price paid in 2003 for negotiated hogs between 9:30 am and 1:30 pm was $51.81/cwt. The average price paid after 1:30 pm and before midnight was $52.15/cwt.

The eastern corn belt price was lower than the national average price in 2003 while the western corn belt price was slightly higher than the national average. Both of these relationships were also present in 2002.

Mandatory price report rules allow packers to exclude five types of payments from the purchase prices they report: premiums for volume, transportation allowances, delivery time bonuses, breed premiums and a premium for NPPC quality assurance. USDA/AMS issues a weekly summary of these allowances that is available at: http://www.ams.usda.gov/mnreports/lm_hg250.txt. For a typical week, packers report paying carcass premiums of zero to $1.50/cwt for volume deliveries, zero to $3.50/cwt for transportation allowance, zero to $4.50/cwt for delivery time, and zero to $18/cwt for breed (presumably for Berkshire hogs). Several packers used to pay a bonus for hogs from producers who participate in the National Pork Board’s Pork Quality Assurance (PQA) program. Most packers now require it as a condition of delivery.

Negotiating a Marketing Contract

When negotiating a marketing contract, there are a number of issues producers should keep in mind. Marketing contracts vary from packer to packer. Most packers offer more than one type of contract. Time and effort will be required for a producer to evaluate and negotiate the most beneficial contract. Marketing contracts offer producers an opportunity to reduce price risk and enhance income relative to the spot market. But, packers aren’t idiots. It’s difficult to negotiate a flexible contract that does both. Producers should have a clear understanding of their goals before making major marketing decisions. For example, some packers prefer for their contract hogs to be delivered early in the morning. A long-term contract with a distant packer can lock a producer into years of sorting and loading hogs hours before the sun comes up. USDA maintains a library of swine marketing contract provisions accessible via internet at: http://scl.gipsa.usda.gov/. The Attorney General of Iowa maintains a site with actual contracts in use in Iowa that is available at: http://www.state.ia.us/government/ag/ag_contracts/.

Type of Marketing Contracts

Perhaps the simplest type of marketing contract is what USDA calls “other market formula,” which is a forward price contract based on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange’s lean hog futures contract. Marketing contracts based on hog futures contracts have been around for a long time. Most packers offer producers the option of locking-in a price for hogs to be delivered in the next few months, if the producer agrees to accept the appropriate futures market contract price adjusted by a packer-specified basis. This type of contract allows producers to reduce market risk while making marketing decisions on a lot-by-lot basis. It also avoids some of the hassle associated with a direct hedge on the futures market. However, producers must still decide when they feel the futures market is favorable to them.

Swine market formula contracts are very popular with producers who live in areas where there are not several packers competing for hogs. Without a strong local market for hogs, it makes good sense to rely on a major market price, such as the Iowa-Minnesota report, as the base price. A formula contract tied to prices in a major hog-producing region reduces the possibility the producer will be disadvantaged by location.

Pork market formula contracts use carcass cutout values or the wholesale price of primal cuts as the basis for establishing the value of the market hog. Some producers find these contracts appealing because the contract is tied closely to the wholesale value of the hog.

USDA’s other purchase agreement category covers a number of contract types. Some packers offer contracts in which the hog price is determined primarily by the cost of feed ingredients, usually corn and soybean meal. The advantage of this type of contract is that the price received for hogs goes up and down with the price of feed, which typically makes up about 60% of the total cost of production. The disadvantage is that they often lock the producer into a fairly tight margin over feed costs.

Another popular marketing contract in USDA’s other purchase agreement category is the window contract. Window contracts typically use a specified spot market price along with a floor price and a ceiling price. When the specified market price drops below the floor price, the packer shares in the price decline by paying an above market price. Conversely, when the specified market price rises above the ceiling price, the producer shares the benefit of the high price with the packer by accepting a below market price for the hogs. For example, a window contract might use the USDA’s morning report of the average hog price in the western corn belt as the base price with a window from $50/cwt to $60/cwt of carcass weight. When the western corn belt price drops below $50/cwt, the contract might call for the packer to pay a price that is midway between the market price and the floor price. When the western corn belt price rises above $60/ cwt, the producer receives a price that is midway between the market price and the ceiling price.

A third type of contract that is gaining popularity is the floor contract. With this arrangement the producer agrees to accept a slightly discounted price for hogs (e.g. 98% of the Iowa-Minnesota price) in exchange for having a guaranteed price floor (e.g. never less than $44/cwt). This type of contract is especially appealing to lenders.

Ledgers

Many marketing contracts include “ledgers” or accrual accounts. With a ledger, the packer keeps track of how the actual price paid under the contract compares to a specified spot market price or target price. The ledger account accumulates a positive balance when the price paid exceeds the specified market or target price. The balance in the ledger account declines when the contract price paid is below the specified market or target price. Some ledger provisions put limits on the size of the ledger account and call for interest to be calculated on the balance in the ledger. At the end of the contract, a settling-up provision requires the producer to extend the contract or compensate the packer in some fashion if the average price paid under the purchase agreement exceeded the target price or the average of the specified spot market price, i.e. the ledger balance is positive. Conversely, the packer will have to compensate the producer in some manner if the average price paid under the purchase agreement falls below the average specified spot market price, i.e. the ledger account is negative. Some contracts have sunset provisions that cause the ledger balance to decline after a set period of time.

In essence, a ledger is a mechanism by which the producer loans money to the packer when hog prices are high and the packer loans money to the producer when hog prices are low. In some early contracts these “loans” were unsecured and difficult to collect. In most recent contracts, ledger balances represent debt that is legally obligated to be repaid. Although USDA does not report it, we know from other sources that a majority of the contract sales in USDA’s “other purchase agreement” category include ledger provisions including about three-fourths of those that use feed prices as the primary price setting mechanism and roughly a quarter of the window contracts.

Price Base for a Contract

Most contracts use a publicly reported price as a base and pay carcass related premiums and discounts from that base price. What base is used has an impact on the final price as Table 3 indicates. During the first two and a half years of USDA’s mandatory price reports, the western corn belt prior day purchased report had a slightly higher average price than the other reports. There is no guarantee, of course, that this will always be the case. Because they are based on fewer hogs, the morning reports are more volatile than the afternoon reports and the regional reports are slightly riskier than the national report.

Length of Contract

An important issue with most marketing contracts is the length of contract. Many packers offer short-term, long-term and “evergreen” contracts. An evergreen contract is terminated when either the producer or the packer gives advance notice; otherwise the contract lasts forever. An assumption that many people make is that long-term contracts are less risky than short-term contracts. This may not be the case. The hog industry is very dynamic. It is impossible to predict exactly what hog markets will be like 7-10 years from now. A long-term contract can lock the producer into a marketing arrangement that becomes less desirable by the year. On the other hand, a producer may find the contract becoming more advantageous over time.

Premiums and Discounts

Some packers are willing to adjust their carcass premium and discount schedule for producers who sign long-term contracts. It can be to the producer’s advantage to negotiate a premium for early morning delivery, or a wider carcass weight target range. Producers should discuss these issues with packers when negotiating marketing contracts.

Flexibility

With long-term contracts, flexibility becomes an issue. Over a period of years, a producer may desire to expand or reduce hog numbers. Packers may close existing slaughter plants or open new ones. Industry standards on slaughter weight and percent lean will change. Contracts should be written to accommodate these changes. It is also wise to include a clause in the contract discussing how disputes will be resolved.

Summary

U.S. hog packing continues to evolve towards fewer and larger packers who rely on marketing contracts and their own production of hogs to supply their slaughter needs. Over one-fifth of U.S. hogs are raised by hog packers and another 65% are under a packer marketing contract. This is a natural evolution for an industry that has low profit margins, a variable supply, and faces a customer base demanding more information and assurances about the product it buys. A close relationship between producers and packers is a necessary part of an efficient and responsive marketing chain. Negotiating a good marketing contract is challenging but will probably serve producers long-term interests better than continuing to rely on the spot market.

References

1. Grimes, G, Plain, R, Meyer, S. U.S. Hog Marketing Contract Study, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Missouri-Columbia, January, 2004.

2. Grimes, G, Plain, R, Meyer, S. Analysis of USDA Mandatory Hog Price Data, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Missouri-Columbia, March 12, 2004.

3. Plain, R, Bullock, B. “The Missouri Livestock Marketing Law” Missouri Farm Financial Outlook 2002, Agricultural Economics Department, University of Missouri, November 2001.

4. Lawrence, J, Grimes, G. Production and Marketing Characteristics of U.S. Pork Producers, 2000, Staff Paper 343, Department of Economics, Iowa State University, August 2001.

Table 1. Barrow and Gilt Purchases by Reporting Packers in 2003. Source: USDA/ AMS Prior Day Slaughter Reports on packers killing 100,000+ hogs/year.

Table 2. Average Barrow and Gilt Prices Paid by Reporting Packers in 2003. Source: USDA/AMS Prior Day Slaughter Reports on packers killing 100,000+ hogs/year.

Table 3. Average Barrow and Gilt Negotiated Prices Paid by Reporting Packers in 2003. Source: USDA/AMS AM, PM and Prior Day Purchase Reports on packers killing 100,000+ hogs/year.

Figure 1. Percent of Barrows and Gilts sold on the Spot Market, 1994-2003.