Resolving Conflict with Employees in Swine Production

Author:

Michael Swan, Washington State University

Reviewers:

Katrina Waters, Texas Tech University;

Melinda Findley, Texas Tech University;

David Doerfert, Texas Tech University

Objectives

- Define conflict.

- Recognize the benefits of the nominal decision making technique.

- Identify how attitude affects individual behavior and group effectiveness.

- Demonstrate interference in communication and the problems it causes.

- Illustrate conflict management and the leader’s role.

- Compare effectively the purposes and objectives of various conflict management theories.

- Appraise similarities and differences in group values, ideas, and beliefs.

- Develop a procedure for managing conflict in your life.

To accomplish these objectives you will complete these activities:

- Read and discuss the theoretical introduction to conflict management and compose a definition of conflict.

- Discuss and summarize the nature of conflict and its implications for groups, teams, and organizations.

- Examine a case study and identify the early warning signs of conflict and the levels of conflict in the situation.

- Participate in a group activity in conflict negotiation using the concepts of conflict management presented in the module.

A Case Study in Conflict Management: He said, She said . . .

Wanda and Juan both work for a Performance Swine Systems. The manager of the operation was originally the leader of a production team for which she interviewed and hired Juan. Wanda, another production team member, also interviewed Juan but strongly opposed hiring him for the team because she thought he was not competent to do the job.

Seven months after Juan was hired, the manager left the team to devote more time to her administrative duties and proposed that Juan and Wanda serve as joint team leaders. Wanda agreed reluctantly with the stipulation that it be made clear she was not working for Juan. The manager consented; Wanda and Juan were to share the team leadership.

Within a month Wanda was angry because Juan was representing himself to others as the leader of the entire team and giving the impression that Wanda was working for him. Now Wanda and Juan are meeting with you to see if you can help them resolve the conflict between them.

Wanda says: “Right after the joint leadership arrangement was reached with the manager, Juan called a meeting of the team without even consulting me about the time or content. He just told me when it was being held and said I should be there. At the meeting Juan reviewed everyone’s duties line by line, including mine, treating me as just another team member working for him. He sends out letters and signs himself as team director, which obviously implies to others that I am working for him.”

Juan says: “Wanda is all hung up with feelings of power and titles. Just because I sign myself as team director doesn’t mean that she is working for me. I don’t see anything to get excited about. What difference does it make? She is too sensitive about everything. I call a meeting and right away she thinks I’m trying to run everything. Wanda has other things to do other projects to run so she doesn’t pay too much attention to this one. She mostly lets things slide. But when I take the initiative to set up a meeting, she starts jumping up and down about how I am trying to make her work for me.”

Discussion Questions

A variety of strategies can be used to help resolve the conflict between Juan and Wanda. As you explore and develop concepts on conflict management presented in this chapter keep this situation in mind. At the conclusion of this chapter you should be able to recognize the warning signs of how to prevent this type of conflict from becoming a reality. But before reading the chapter, put yourself in the position of mediator between Juan and Wanda and consider the following questions:

- Juan and Wanda seem to have several conflicts occurring simultaneously. Identify as many of these individual conflicts as possible.

- Are there any general statements you can make about the overall nature of the conflict between Juan and Wanda?

- What are the possible ways to deal with the conflict between Juan and Wanda (not just the ones that you would recommend, but all of the options)?

- Given the choices identified in #3, what is the best way for Juan and Wanda to deal with the conflict between them?

- Given all the benefits of retrospection, what could or should have been done to avoid this conflict in the first place?

Introduction to Theories of Conflict Resolution

What is conflict? Is it the same as a disagreement or an argument? Typically, conflict is characterized by three elements: 1) interdependence, 2) interaction, and 3) incompatible goals. We can define conflict as the interaction of interdependent people who perceive a disagreement about goals, aims, and values, and who see the other party as potentially interfering with the realization of these goals. Conflict is a social phenomenon that is woven into the fabric of human relationships; therefore, it can only be expressed and manifested through communication. We can only come into conflict with people with whom we are interdependent; that is, only when we become dependent on one another to meet our needs or goals does conflict emerge.

Conflicts are differentiated in a number of ways. One method of distinguishing among conflict situations is based on the context in which the conflict occurs. Barge (1994) indicates that traditionally conflict is viewed as occurring in the following three contexts:

interpersonal conflict exists between two individuals within a group.

intergroup conflict occurs between two groups within the larger social system.

interorganizational conflict occurs between two organizations.

Understanding Conflict

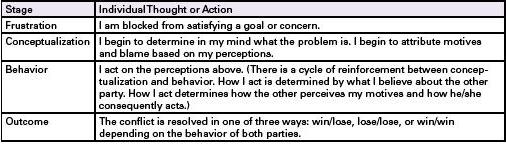

Most authorities claim some conflict is inevitable in human relationships where people and groups are inter-dependent. Clashes occur more often over perceived differences than over real ones. People anticipate blocks to achieving their goals that may or may not be there. Thus conflict can be defined as two or more people independently perceiving that what each one wants is incompatible with what the other one wants. There is a normal process of development in any conflict and this process tends to be cyclical, repeating itself over and over. At each stage of the cycle, the potential for conflict grows stronger. In the table below, each stage of the conflict development process is described in terms of the thoughts or actions an individual experiences as the conflict develops.

Conflict often results when we fail to check our perceptions and assumptions about the other party’s attitudes and motives. Our subsequent behavior and the outcome of the conflict are directly determined by the conceptualization phase.

We act on our beliefs about the other party. For example, we may decide that the person rejected our idea because he or she is threatened by or does not like us when, in fact, we did not communicate clearly or give enough information. We will respond quite differently depending on which case we believe to be true. Rees (1991) suggests that conflict, like power, is neither good nor bad. It is what we do with it that makes the difference.

Although conflict is generally viewed in a negative way and as something to avoid, when appropriately managed it can generate beneficial results. Conflict management theorists distinguish between constructive and destructive conflict. Constructive conflict is functional because it helps members accomplish goals and generate new insights into old problems. Destructive conflict is dysfunctional because it negatively affects group members by disrupting their activity. Bennis (1989) lists several characteristics that distinguish constructive and destructive conflict.

Constructive Conflict:

- allows constructive change and growth to occur within a system or group.

- provides the opportunity for resolving problems associated with diversity of opinion.

- provides a forum for unifying the group.

- enhances group productivity.

- enhances group commitment.

Destructive Conflict:

- develops when lack of common agreement leads to negativism.

- leads to hardening of respective positions and diminished likelihood of a resolution.

- causes the group to divide into camps, each supporting a different position.

- results in a decrease in group productivity, satisfaction, and commitment.

Misconceptions about Conflict

Smith & Anderson (1989) suggest that people still hold negative opinions about the advisability of conflict resolution because of the following misconceptions:

- Harmony is normal and conflict is abnormal. This belief is erroneous. Conflict is normal; in fact, it is inevitable. Whenever two people must interact in order to achieve goals, their subjective views and opinions about how to best achieve those goals will lead to conflict of some degree. Harmony happens only when conflict is acknowledged and resolved.

- Conflicts and disagreements are the same. Disagreement is usually temporary and limited, stemming from misunderstanding or differing views about a specific issue rather than a situation’s underlying values and goals. Conflicts are more serious and usually are rooted in incompatible goals.

- Conflict is the result of “personality problems.“ Personalities themselves are not cause for conflict. While people of different personality types may approach situations differently, true conflict develops from and is reflected in behavior, not personality.

- Conflict and anger are the same thing. While conflict and anger are closely merged in most people’s minds, they don’t necessarily go hand in hand. Conflict involves both issues and emotions the issue and the participants determine what emotions will be generated. Serious conflicts can develop that do not necessarily result in anger. Other emotions are just as likely to surface: fear, excitement, sadness, frustration, and others.

Getting beyond the misconceptions described above is crucial to effective conflict resolution.

Levels of Conflict

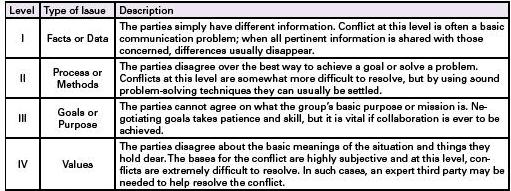

One thing that determines the depth and complexity of conflict is the type of basic issue at stake. Most experts identify four levels of issues that may be the bases for conflict. Conflicts that escalate to higher levels become more complex and thus more difficult to resolve.

Warning Signs

Being aware of conflict warning signs can minimize conflict situations. The following social relationship characteristics should alert us to the potential for conflict.

- Ambiguous Jurisdictions. If divisions of responsibility and authority are unclear, the possibility of conflict increases.

- Conflict of interest. Competition for perceived scarce resources (or rewards) escalates conflict possibilities.

- Communication Barriers. Lack of communication, misunderstanding in terminology, unwillingness to listen to another person, etc., increase conflict possibilities.

- Overdependency of One Party. If one person depends too heavily on another for information or assistance, conflict is more apt to occur.

- Differentiation in Organization. The greater the degree of differentiation in a group (i.e., levels of authority, types, and numbers of specific tasks), the greater the potential for conflict.

- Association of the Parties. The more individuals interact, both informally and in decision making situations, the greater the opportunity for conflict. However, major incidents of conflict decrease as interaction increases.

- Need for Consensus. When all parties must agree on the outcome, disagreements tend to escalate.

- Behavior Regulations. Conflicts are greater when controls like rules, regulations, and formal policies are imposed.

- Unresolved Prior Conflicts. As the number of past unresolved conflicts increases, so does the possibility for more conflicts in the future. (This underlines the importance of managing conflicts at their earliest stages, since they do not go away!)

Phases of Conflict Management

When parties in conflict agree that conflict resolution is needed, they are more likely to succeed if they move through prescribed phases to reach resolution (Johnson & Johnson, 1994).

- Collect data. Know exactly what the conflict is about and objectively analyze the behavior of parties involved.

- Probe. Ask open ended questions, actively listen, facilitate communication.

- Save face. Work toward a win/win resolution. Avoid embarrassing either party. Maintain an objective (not emotional) level.

- Discover common interests. This will help individuals redefine dimensions of the conflict and perhaps bring about a compromise.

- Reinforce. Give additional support to common ideas of both parties and know when to use the data collected.

- Negotiate. Suggest partial solutions or compromises identified by both parties. Continue to emphasize common goals of both parties involved.

- Solidify adjustments. Review, summarize, and confirm areas of agreement. Resolution involves compromise.

Strategies for Coping With Conflict

There are a variety of strategies available for dealing with conflict. Some of us are more comfortable with some of these strategies than with others, but we all can be better conflict managers if we develop skills to implement several strategies and adapt resolution strategies to suit the particular conflict situation. Johnson & Johnson (1994) describe five possible approaches to conflict management: avoidance, accommodation, compromise, competition, and collaboration.

Avoidance

Avoidance occurs when an individual fails to address the conflict, but rather sidesteps, postpones, or simply withdraws. Some people attempt to avoid conflict by postponing it, hiding their feelings, changing the subject, leaving the room, or quitting the project. Use avoidance when:

- The stakes aren’t that high and you don’t have anything to lose.

- You don’t have time to deal with it.

- The context isn’t suitable to address the conflict it isn’t the right time or place.

- More important issues are pressing.

- You see no chance of getting your concerns met.

- You would have to deal with an angry, hot headed person.

- You are totally unprepared, taken by surprise, and you need time to think and collect information.

- You are too emotionally involved and the others around you can solve the conflict more successfully.

Avoidance may not be appropriate when the issue is very important and postponing resolution will only make matters worse. Avoiding conflict is generally not satisfying to the individuals involved in a conflict, nor does it help the group resolve a problem.

Accommodation

Accommodation is a convenient strategy for satisfying an immediate need for individuals or the group. It emphasizes the things conflicting parties have in common, de emphasizes the differences, and helps groups review their common purpose in the midst of conflict. Use accommodation when:

- The issue is more important to the other person than it is to you.

- You discover that you are wrong.

- Continued competition would be detrimental and you know you can’t win.

- Preserving harmony without disruption is the most important consideration.

Accommodation should NOT be used if an important issue is at stake which needs to be addressed immediately.

Compromise

The objective of compromise is to find an expedient, mutually acceptable solution which partially satisfies both parties. It falls in the middle between competition and accommodation. Compromise gives up more than competition does, but less than accommodation. Compromise is appropriate when all parties are satisfied with getting part of what they want and are willing to be flexible. Compromise is mutual: all parties should receive something, and all parties should give something up. Use compromise when:

- The goals are moderately important but not worth the use of more assertive strategies.

- People of equal status are equally committed.

- You want to reach temporary settlement on complex issues.

- You want to reach expedient solutions on important issues.

- You need a back up mode when competition or collaboration don’t work.

Compromise doesn’t work when initial demands are too great from the beginning and there is no commitment to honor the compromise.

Competition

An individual who employs the competition strategy pursues his or her own concerns at the other person’s expense. This is a power oriented strategy used in situations in which eventually someone wins and someone loses. Competition enables one party to win. Before using competition as a conflict resolution strategy, you must decide whether or not winning this conflict is beneficial to individuals or the group. Use competition when:

- You know you are right.

- You need a quick decision.

- You meet a steamroller type of person and you need to stand up for your own rights.

Competition will not enhance a group’s ability to work together. It reduces cooperation.

Collaboration

Collaboration is the opposite of avoidance. It is characterized by an attempt to work with the other person to find some solution which fully satisfies the concerns of both. This strategy requires you to identify the underlying concerns of the two individuals in conflict and find an alternative which meets both sets of concerns. This strategy encourages teamwork and cooperation within a group. Collaboration does not create winners and losers and does not presuppose power over others. The best decisions are made by collaboration. Use collaboration when:

- Others’ lives are involved.

- You don’t want to have full responsibility.

- There is a high level of trust.

- You want to gain commitment from others.

- You need to work through hard feelings, animosity, etc.

Collaboration may not be the best strategy to use if time is limited and people must act before they can work through their conflict, or there is not enough trust, respect or communication among the group for collaboration to occur.

Creative Ways to Manage Conflict

Conflict of some degree is inevitable when individuals or groups work together. Before conflict evolves, decide to take positive steps to manage it. When it does occur, discuss it openly with the group. Here are some useful guidelines to follow when managing conflict:

- Deal with one issue at a time. More than one issue may be involved in the conflict, but someone in the group needs to provide leadership to identify the issues involved. Then address one issue at a time to make the problem manageable.

- If there is a past problem blocking current communication, list it as one of the issues in this conflict. It may have to be dealt with before the current conflict can be resolved.

- Choose the right time for conflict resolution. Individuals have to be willing to address the conflict. We are likely to resist if we feel we are being forced into negotiations.

- Avoid reacting to unintentional remarks. Words like always and never maybe said in the heat of battle and do not necessarily convey what the speaker means. Anger will increase the conflict rather than bring it closer to resolution.

- Avoid resolutions that come too soon or too easily. People need time to think about all possible solutions and the impact of each. Quick answers may disguise the real problem. All parties need to feel some satisfaction with the resolution if they are to accept it. Conflict resolutions should not be rushed.

- Avoid name calling and threatening behavior. Don’t corner the opponent. All parties need to preserve their dignity and self respect. Threats usually increase the conflict and payback can occur some time in the future when we least expect it.

- Agree to disagree. In spite of your differences, if you maintain respect for one another and value your relationship, you will keep disagreements from interfering with the group.

- Don’t insist on being right. There are usually several right solutions to every problem.

Humor and Conflict

Laughter can effectively relieve tension in conflict situations. A well timed joke can refocus conflict negotiations in a positive direction. Laughter gives people time to rethink their positions and see alternatives that may not have been obvious before (Westcott, 1988).

A leader can read a humorous story at the beginning of a meeting to set the tone or be prepared with a humorous example to use in case conflict occurs. Laughing together helps individuals accept differences and still enjoy one another as group members.

Humor is most effective when it relates to the situation at hand. The best source of humor is personal experience and it’s usually safe to use oneself as target of the humor. However, humor should never belittle or insult anyone. Use humor to support talent within the group rather than as a way to cover lack of skill.

Summary

Elected leaders of an organization have a strong influence on relationships within the group. That influence may have a positive or negative effect on how the group functions. The group should elect officers regularly to share the leadership and reduce the possibility of any single member creating a negative environment for a long term.

Leaders for the 1990s and beyond should learn how to manage and use conflict creatively for the betterment of communities, organizations, and personal relationships. We don’t need to be devastated by conflict when we can learn to manage it and use the energy it produces. Leaders confront a variety of relational problems as groups and teams develop over time. Some problems may include defining roles, motivating followers, and managing conflict. Such problems can be overcome by leadership that recognizes them and takes appropriate action to resolve them. All leaders can facilitate resolving relational issues through conflict management, bargaining, and feedback.

References

Barge, J. Kevin. (1994). Leadership communication skills for organizations and groups. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Bennis, Warren. (1989). Why leaders can’t lead. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Carter, R.I., & Spotanski, D.R. (1991). Leadership and personal development: A resource packet. Ames, IA: Leadership Studies.

Johnson, David W., & Johnson, Frank P. (1994). Joining together group theory and group skills. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Pfeiffer & Company. (1991). 1991 Annual: Developing human resources. San Diego: Pfeiffer & Company.

Pfeiffer & Company. (1994). 1994 Annual: Developing human resources. San Diego: Pfeiffer & Company.

Rees, Fran. (1991). How to lead work teams. San Diego: Pfeiffer & Company.

Shinn, George. (1986). Leadership development. New York: McGraw Hill.

Smith, Wilma F., & Andrews, Richard L. (1989). Instructional leadership: How principals make a difference. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Westcott, Jean M. (1988). Humor and the effective work group. In 1988 Annual: Developing human resources. San Diego: Pfeiffer & Company.